Ancient Catapults: Some Hypotheses Reexamined

By Duncan B. Campbell

Hesperia, Vol.80 (2011)

Abstract: Recent summaries and overviews of the development of ancient catapults have mistaken working hypotheses for established fact. Key areas of misunderstanding include the invention of the catapult, the development of the torsion principle, the meaning of the terms euthytone and palintone, and the possible use of sling bullets as catapult missiles. A critical reexamination of these questions, setting them within the framework of the known facts, reveals the fragility of the accepted history of the catapult, as currently presented in general handbooks.

Introduction: In the field of classical archaeology, a new and interesting hypothesis can be useful in jogging a tired debate onto a new path for exploration. But some hypotheses, attractive at first sight, turn out to be dead ends because they employ fundamentally flawed reasoning.

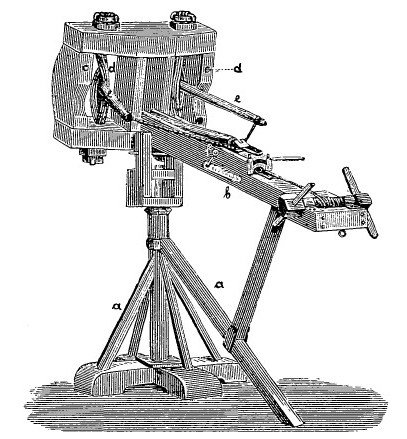

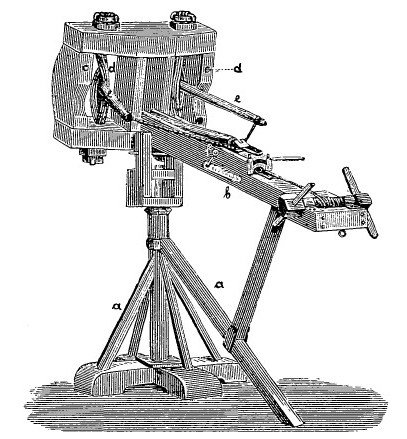

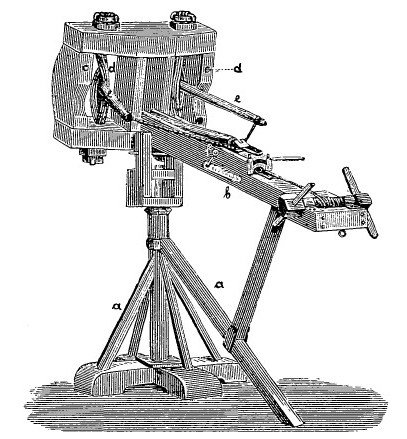

The study of ancient artillery provides a well-known example of a badly formulated hypothesis, and demonstrates the unwelcome consequences that can ensue. In 1867, a Greek text entitled Ἥρωνος χειροβαλλίστρας κατασκευὴ καὶ συμμετρία (“Heron, Construction and Dimensions of the Hand-Ballista,” nowadays usually called “Heron’s Cheiroballistra”) was published in a collection of ancient military treatises. It appeared to describe the component parts of a small catapult. An initial attempt by the French engineer Victor Prou to build the device was condemned as fanciful, and his interpretation of the text was subsequently discredited by the German philologist Rudolf Schneider. Schneider’s bold hypothesis, that the text labeled with the name of a catapult (for what else could a cheiroballistra be?) was, in fact, no such thing, effectively derailed the study of the iron-framed ballista and took it down a blind alleyway, where it remained for 60 years.

It could have ended otherwise. The fraternity of artillery scholars chose to favor Schneider’s opinion over those of his critics, chiefly Karl Tittel, who urged that “the technical terms point unmistakably to the construction of an artillery-piece.” It was only after the text was rescued by Eric Marsden that it was again taken seriously as a description of a catapult.

It could have ended otherwise. The fraternity of artillery scholars chose to favor Schneider’s opinion over those of his critics, chiefly Karl Tittel, who urged that “the technical terms point unmistakably to the construction of an artillery-piece.” It was only after the text was rescued by Eric Marsden that it was again taken seriously as a description of a catapult.

If we are to maintain the rigor of our discipline, we must be careful to rein in the kind of “blue-sky” thinking that Schneider freely employed, or at least subject it to careful scrutiny. In particular, at a time when several authors have recently presented their versions of the development of the catapult for a wider readership, we must ensure that any hypotheses are firmly based on evidence, not on groundless speculation.

Click here to read this article from Hesperia

Sponsored Content

Ancient Catapults: Some Hypotheses Reexamined

By Duncan B. Campbell

Hesperia, Vol.80 (2011)

Abstract: Recent summaries and overviews of the development of ancient catapults have mistaken working hypotheses for established fact. Key areas of misunderstanding include the invention of the catapult, the development of the torsion principle, the meaning of the terms euthytone and palintone, and the possible use of sling bullets as catapult missiles. A critical reexamination of these questions, setting them within the framework of the known facts, reveals the fragility of the accepted history of the catapult, as currently presented in general handbooks.

Introduction: In the field of classical archaeology, a new and interesting hypothesis can be useful in jogging a tired debate onto a new path for exploration. But some hypotheses, attractive at first sight, turn out to be dead ends because they employ fundamentally flawed reasoning.

The study of ancient artillery provides a well-known example of a badly formulated hypothesis, and demonstrates the unwelcome consequences that can ensue. In 1867, a Greek text entitled Ἥρωνος χειροβαλλίστρας κατασκευὴ καὶ συμμετρία (“Heron, Construction and Dimensions of the Hand-Ballista,” nowadays usually called “Heron’s Cheiroballistra”) was published in a collection of ancient military treatises. It appeared to describe the component parts of a small catapult. An initial attempt by the French engineer Victor Prou to build the device was condemned as fanciful, and his interpretation of the text was subsequently discredited by the German philologist Rudolf Schneider. Schneider’s bold hypothesis, that the text labeled with the name of a catapult (for what else could a cheiroballistra be?) was, in fact, no such thing, effectively derailed the study of the iron-framed ballista and took it down a blind alleyway, where it remained for 60 years.

If we are to maintain the rigor of our discipline, we must be careful to rein in the kind of “blue-sky” thinking that Schneider freely employed, or at least subject it to careful scrutiny. In particular, at a time when several authors have recently presented their versions of the development of the catapult for a wider readership, we must ensure that any hypotheses are firmly based on evidence, not on groundless speculation.

Click here to read this article from Hesperia

Sponsored Content