Since the 16th century, Basel has been home to a mysterious papyrus. With mirror writing on both sides, it has puzzled generations of researchers. A research team from the University of Basel has now discovered that it is an unknown medical document from late antiquity. The text was likely written by the famous Roman physician Galen.

The Basel papyrus collection comprises 65 papers in five languages, which were purchased by the university in 1900 for the purpose of teaching classical studies – with the exception of two papyri. These arrived in Basel back in the 16th century, and likely formed part of Basilius Amerbach’s art collection.

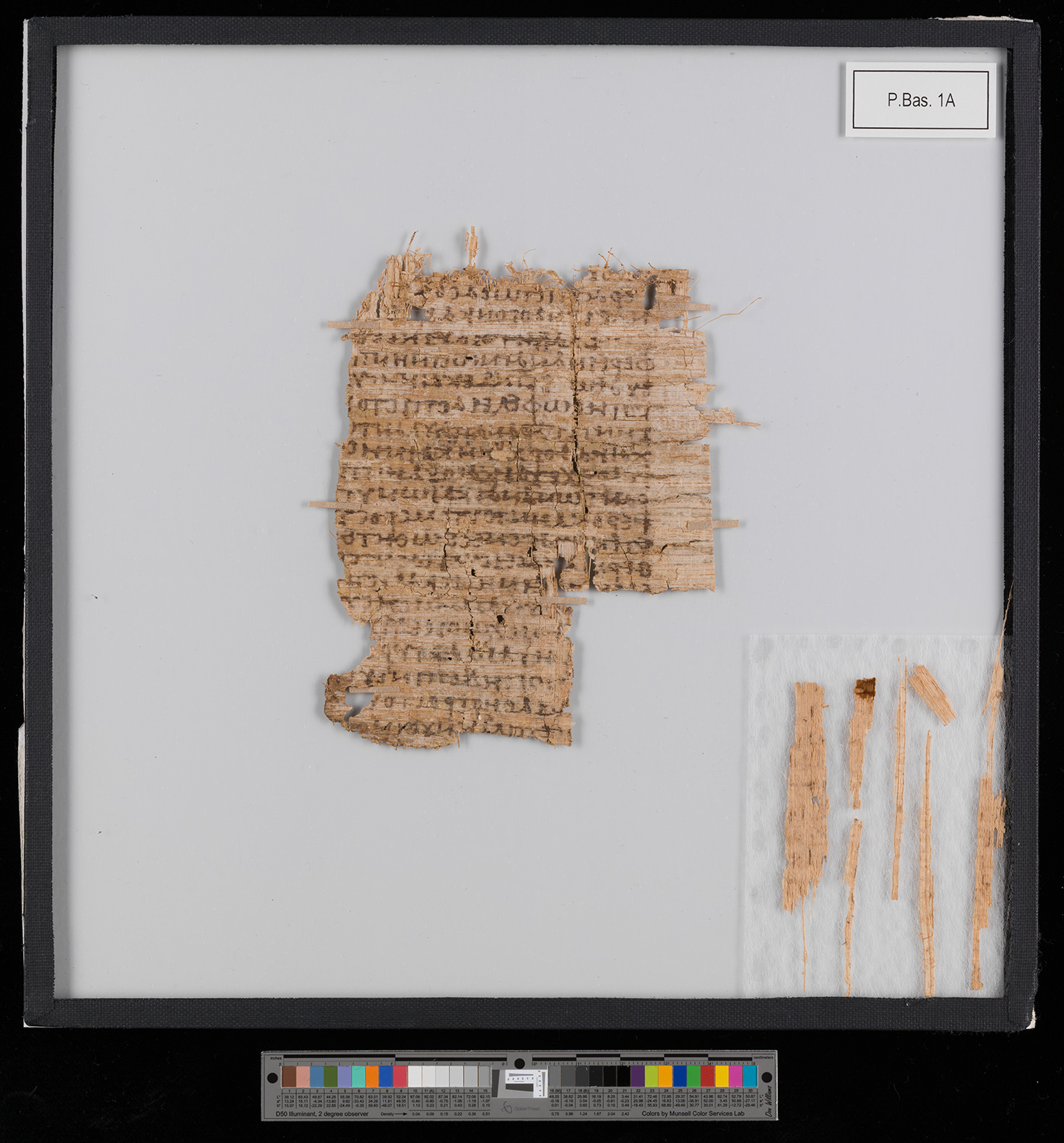

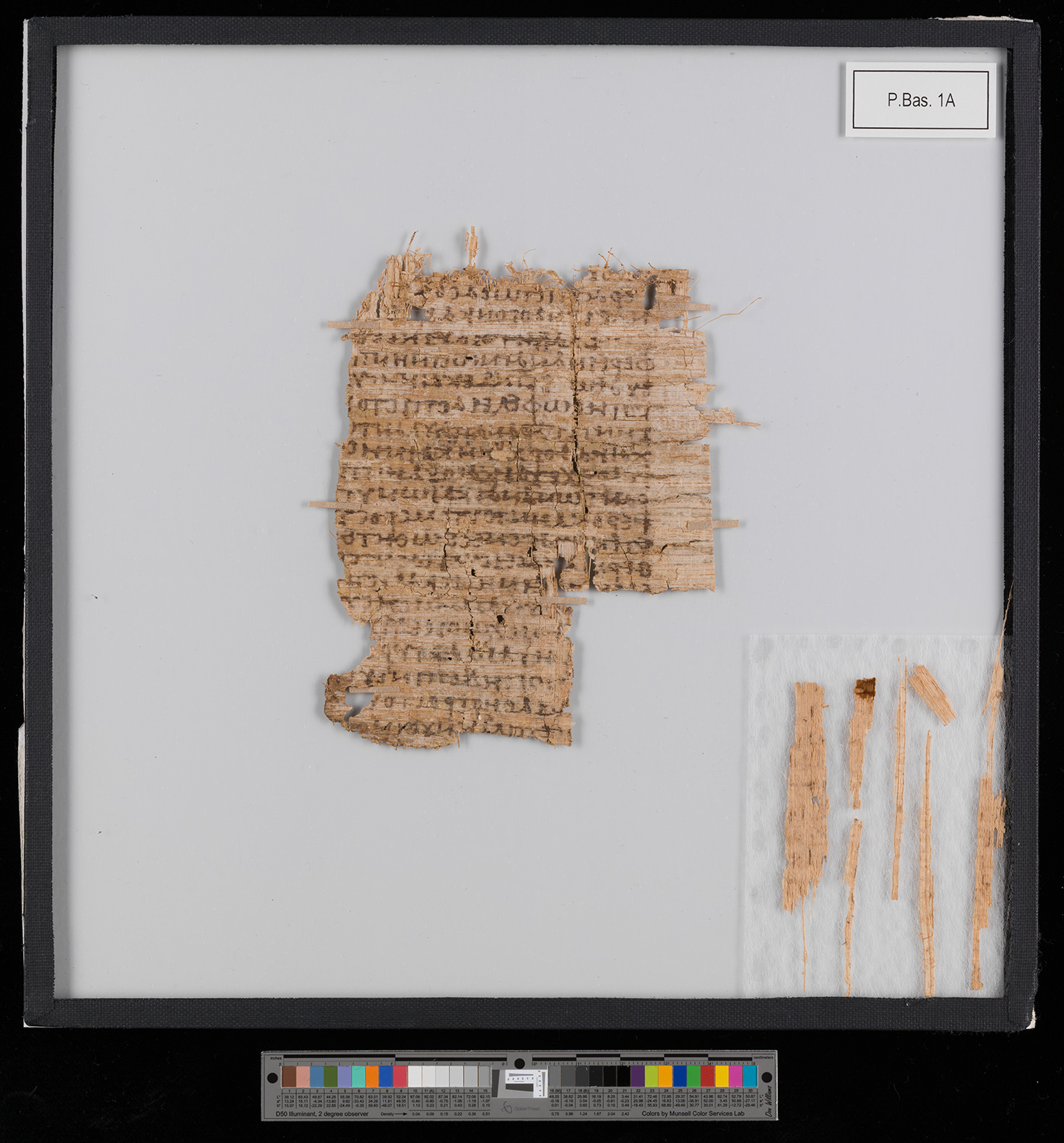

One of these Amerbach papyri was regarded until now as unique in the world of papyrology. With mirror writing on both sides, it has puzzled generations of researchers. It was only through ultraviolet and infrared images produced by the Basel Digital Humanities Lab that it was possible to determine that this 2,000-year-old document was not a single papyrus at all, but rather several layers of papyrus glued together. A specialist papyrus restorer was brought to Basel to separate the sheets, enabling the Greek document to be decoded for the first time.

“This is a sensational discovery,” says Sabine Huebner, Professor of Ancient History at the University of Basel. “The majority of papyri are documents such as letters, contracts and receipts. This is a literary text, however, and they are vastly more valuable.”

What’s more, it contains a previously unknown text from antiquity. “We can now say that it’s a medical text from late antiquity that describes the phenomenon of ‘hysterical apnea’,” says Huebner. “We therefore assume that it is either a text from the Roman physician Galen, or an unknown commentary on his work.” After Hippocrates, Galen is regarded as the most important physician of antiquity.

The decisive evidence came from Italy – an expert saw parallels to the famous Ravenna papyri from the chancery of the Archdiocese of Ravenna. These include many antique manuscripts from Galen, which were later used as palimpsests and written over. The Basel papyrus could be a similar case of medieval recycling, as it consists of multiple sheets glued together and was probably used as a book binding. The other Basel Amerbach papyrus in Latin script is also thought to have come from the Archdiocese of Ravenna. At the end of the 15th century, it was then stolen from the archive and traded by art collectors as a curiosity.

Utilizing digital opportunities in research

Huebner made the discovery in the course of an editing project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. For three years, she has been working with an interdisciplinary team in collaboration with the University of Basel’s Digital Humanities Lab to examine the papyrus collection, which in the meantime has been digitalized, transcribed, annotated and translated. The project team has already presented the history of the papyrus collection through an exhibition in the University Library last year. They plan to publish all their findings at the start of 2019.

With the end of the editing project, the research on the Basel papyri will enter into a new phase. Huebner hopes to provide additional impetus to papyrus research, particularly through sharing the digitalized collection with international databases. As papyri frequently only survive in fragments or pieces, exchanges with other papyrus collections are essential. “The papyri are all part of a larger context. People mentioned in a Basel papyrus text may appear again in other papyri, housed for example in Strasbourg, London, Berlin or other locations. It is digital opportunities that enable us to put these mosaic pieces together again to form a larger picture.”

Sponsored Content

Since the 16th century, Basel has been home to a mysterious papyrus. With mirror writing on both sides, it has puzzled generations of researchers. A research team from the University of Basel has now discovered that it is an unknown medical document from late antiquity. The text was likely written by the famous Roman physician Galen.

The Basel papyrus collection comprises 65 papers in five languages, which were purchased by the university in 1900 for the purpose of teaching classical studies – with the exception of two papyri. These arrived in Basel back in the 16th century, and likely formed part of Basilius Amerbach’s art collection.

One of these Amerbach papyri was regarded until now as unique in the world of papyrology. With mirror writing on both sides, it has puzzled generations of researchers. It was only through ultraviolet and infrared images produced by the Basel Digital Humanities Lab that it was possible to determine that this 2,000-year-old document was not a single papyrus at all, but rather several layers of papyrus glued together. A specialist papyrus restorer was brought to Basel to separate the sheets, enabling the Greek document to be decoded for the first time.

“This is a sensational discovery,” says Sabine Huebner, Professor of Ancient History at the University of Basel. “The majority of papyri are documents such as letters, contracts and receipts. This is a literary text, however, and they are vastly more valuable.”

What’s more, it contains a previously unknown text from antiquity. “We can now say that it’s a medical text from late antiquity that describes the phenomenon of ‘hysterical apnea’,” says Huebner. “We therefore assume that it is either a text from the Roman physician Galen, or an unknown commentary on his work.” After Hippocrates, Galen is regarded as the most important physician of antiquity.

The decisive evidence came from Italy – an expert saw parallels to the famous Ravenna papyri from the chancery of the Archdiocese of Ravenna. These include many antique manuscripts from Galen, which were later used as palimpsests and written over. The Basel papyrus could be a similar case of medieval recycling, as it consists of multiple sheets glued together and was probably used as a book binding. The other Basel Amerbach papyrus in Latin script is also thought to have come from the Archdiocese of Ravenna. At the end of the 15th century, it was then stolen from the archive and traded by art collectors as a curiosity.

Utilizing digital opportunities in research

Huebner made the discovery in the course of an editing project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. For three years, she has been working with an interdisciplinary team in collaboration with the University of Basel’s Digital Humanities Lab to examine the papyrus collection, which in the meantime has been digitalized, transcribed, annotated and translated. The project team has already presented the history of the papyrus collection through an exhibition in the University Library last year. They plan to publish all their findings at the start of 2019.

With the end of the editing project, the research on the Basel papyri will enter into a new phase. Huebner hopes to provide additional impetus to papyrus research, particularly through sharing the digitalized collection with international databases. As papyri frequently only survive in fragments or pieces, exchanges with other papyrus collections are essential. “The papyri are all part of a larger context. People mentioned in a Basel papyrus text may appear again in other papyri, housed for example in Strasbourg, London, Berlin or other locations. It is digital opportunities that enable us to put these mosaic pieces together again to form a larger picture.”

Sponsored Content