The Transformation of Athenian Theatre Culture around 400 BC

By Klaus Junker

The Pronomos Vase and its Context, edited by Oliver Taplin and Rosie Wyles (Oxford University Press, 2010)

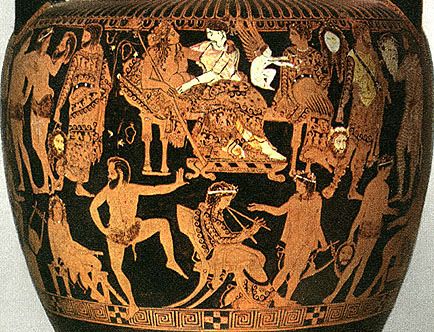

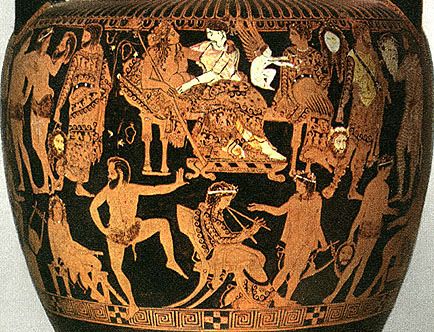

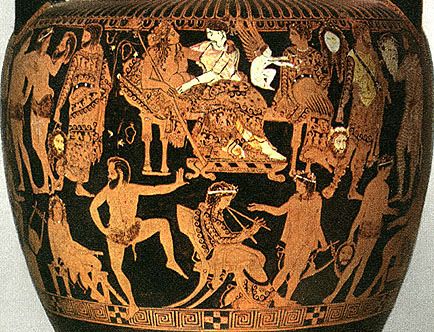

Abstract: The Pronomos krater undoubtedly marks the high point of the production of Greek ‘theatre vases’. However, it is perhaps not exaggerated to maintain that this splendid show piece can at the same time be seen as testimony to and a symptom of a great change or – depending on one’s point of view – even a crisis in Athenian theatre culture. With regard to its actual imagery, three aspects are particularly noteworthy. First: in not reproducing a scene from the play, the emphasis is transferred from the impact of the actual theatrical performance to the theatre as an institution; second: the disposition of the protagonists emphasises two sources of authority with Dionysos as the inspiring patron of the theatre and the citizens of the polis as the promoters of the performances; third: the emphasis on the satyr play is explained principally by their visual and semantic effectiveness. While it certainly cannot be said that the Pronomos vase ‘has nothing to do with drama’, it has, I believe, quite a lot to do with a general development in Classical Athens, one that changed dramatic performances into a stage upon which social distinction and advancement could be acquired. My brief survey of the relevant monuments, choregic and otherwise, is intended to give an idea of the enormous dynamics of this process. In retrospect, the festive gathering on the Pronomos krater represents both the farewell gathering for the theatre as a forum where polis citizens engaged in intellectual exchange, and a welcome party for the theatre as a means of individual self-praise and promotion in the public arena of the city of Athens.

Introduction: The Pronomos Vase was produced towards the end of the fifth century, the period when Athenian theatre culture was undergoing a profound transformation. A number of contemporary—or at least ancient—literary references provide some information about the nature of theatre productions of that time. First, the fact that none of the poets who followed the three tragedians Aischylos, Sophokles, and Euripides produced a tragedy that the ancients considered worth copying enough for it to survive. Secondly, Aristophanes, who in his Frogs of 405, has Dionysos announce that he finds it difficult to name a poet of standing:the best are dead, and those still living bad—an allusion to the fact that both Sophokles and Euripides had passed away a short time previously. Thirdly, the decision taken in 386 to include plays by the three great tragic poets in addition to the new pieces performed on the occasion of the Great Dionysia. This a mounted to an official differentiation between contemporary works and those from the Golden Age of the past.

All this would seem to attest to a general decline of the theatre in Athens during the fourth century, yet there is also evidence which points in the opposite direction. The theatre ‘machinery’— as one might call the joint effort of hundreds of people to produce a splendid festival every year — continued and indeed probably became even more elaborate. The changes in structural organization and cultural attitudes in the Athenian theatre world can best be characterized by the following three terms.

All this would seem to attest to a general decline of the theatre in Athens during the fourth century, yet there is also evidence which points in the opposite direction. The theatre ‘machinery’— as one might call the joint effort of hundreds of people to produce a splendid festival every year — continued and indeed probably became even more elaborate. The changes in structural organization and cultural attitudes in the Athenian theatre world can best be characterized by the following three terms.

Click here to read this article from Academia.edu

Sponsored Content

The Transformation of Athenian Theatre Culture around 400 BC

By Klaus Junker

The Pronomos Vase and its Context, edited by Oliver Taplin and Rosie Wyles (Oxford University Press, 2010)

Abstract: The Pronomos krater undoubtedly marks the high point of the production of Greek ‘theatre vases’. However, it is perhaps not exaggerated to maintain that this splendid show piece can at the same time be seen as testimony to and a symptom of a great change or – depending on one’s point of view – even a crisis in Athenian theatre culture. With regard to its actual imagery, three aspects are particularly noteworthy. First: in not reproducing a scene from the play, the emphasis is transferred from the impact of the actual theatrical performance to the theatre as an institution; second: the disposition of the protagonists emphasises two sources of authority with Dionysos as the inspiring patron of the theatre and the citizens of the polis as the promoters of the performances; third: the emphasis on the satyr play is explained principally by their visual and semantic effectiveness. While it certainly cannot be said that the Pronomos vase ‘has nothing to do with drama’, it has, I believe, quite a lot to do with a general development in Classical Athens, one that changed dramatic performances into a stage upon which social distinction and advancement could be acquired. My brief survey of the relevant monuments, choregic and otherwise, is intended to give an idea of the enormous dynamics of this process. In retrospect, the festive gathering on the Pronomos krater represents both the farewell gathering for the theatre as a forum where polis citizens engaged in intellectual exchange, and a welcome party for the theatre as a means of individual self-praise and promotion in the public arena of the city of Athens.

Introduction: The Pronomos Vase was produced towards the end of the fifth century, the period when Athenian theatre culture was undergoing a profound transformation. A number of contemporary—or at least ancient—literary references provide some information about the nature of theatre productions of that time. First, the fact that none of the poets who followed the three tragedians Aischylos, Sophokles, and Euripides produced a tragedy that the ancients considered worth copying enough for it to survive. Secondly, Aristophanes, who in his Frogs of 405, has Dionysos announce that he finds it difficult to name a poet of standing:the best are dead, and those still living bad—an allusion to the fact that both Sophokles and Euripides had passed away a short time previously. Thirdly, the decision taken in 386 to include plays by the three great tragic poets in addition to the new pieces performed on the occasion of the Great Dionysia. This a mounted to an official differentiation between contemporary works and those from the Golden Age of the past.

Click here to read this article from Academia.edu

Sponsored Content